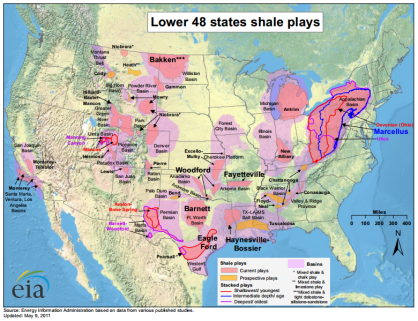

In recent years, hydraulic fracturing has been the source of much enthusiasm and heated debate because of the energy it ultimately provides and the environmental impacts that come along with it. The history of hydraulic fracturing can be traced back to the 1940s, but it did not become prominent until 2003 when large resource companies began exploring huge deposits (called plays) of a type of natural gas called shale gas.

Source: Energy Information Administration

Source: Energy Information Administration

Natural gas is primarily composed of methane and burns cleaner than oil or coal. Ultimately, it releases lower amounts of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide. Sounds good, right? Cleaner fuel, less greenhouse gases- it’s what we want. However, the process of removing shale gas, hydraulic fracturing, may be doing more harm than good- because of policy reasons.

Source: ProPublica

Source: ProPublica

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a relatively simple process (see figure below). In recent years, the most controversial part of this process is the chemical mixing. Many are concerned that this water mixture may contaminate groundwater sources when it is injected into the ground, and rightly so. In this report by the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce Minority Staff, they state that “more than 2500” products were used in mixing, including “750 chemicals and other components”. However, recent studies (here, here, and here) have shown that it is not the chemicals that are contaminating groundwater but methane from gas leaks in the wells.

Source: ProPublica

Source: ProPublica

In 1947, The Safe Drinking Water Act (SWDA) was passed and the EPA’s Underground Injection Control (UIC) Program was created. UIC regulates injection wells to prevent contamination of underground drinking water sources. If there are already regulations in place to prevent such contamination, why do we have so much contamination from fracking? It is because fracking was specifically exempt from the EPA’s authority and regulations in 2005 when the Energy Policy Act was passed (except when diesel fuels are used). Why? The EPA conducted a study in 2004 to analyze the risk of hydraulic fracturing for coalbed methane production on drinking water sources. They “reported that the risk was small, except where diesel was used” and stated that “regulation was not needed”.

Today, we are starting to see how wrong they were. The 112th Congress introduced the Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals Act (FRAC Act) in 2011 for the second time. The FRAC Act would repeal the exemption of fracking from the EPAct and would amend the term “underground injection” to include the liquid mixtures used specifically in hydraulic fracturing. The 2011 Act went nowhere, but there is still hope for groundwater everywhere. The FRAC Act was reintroduced for a third time on June 11, 2013.

A few questions: How familiar are you with fracking? Have you ever seen a fracking site? Did you know about the groundwater contamination issues from fracking, or do you know someone who has dealt with them personally? Do you use natural gas in your home or some area of your life? Do you think the EPA’s study for coalbed methane was capable of judging the impacts of fracking natural gas? What do you think about the FRAC Act?